The 2023 Ladder of Reading & Writing Update

WHY THE 2023 UPDATE?

- The science of reading continues to evolve – both new research and important insights into older research have resulted in an improved understanding of how we might maximize the quality of instruction

- How we teach reading and writing is undergoing needed changes – yet this may be resulting in the adoption of practices and procedures less effective than teachers realize (practices not actually supported in the science)

- I want to ensure my widely-used infographic best represents the full range of learner needs with clarity, providing information grounded in previous research while recognizing ongoing research

WHAT ARE THE CHANGES?

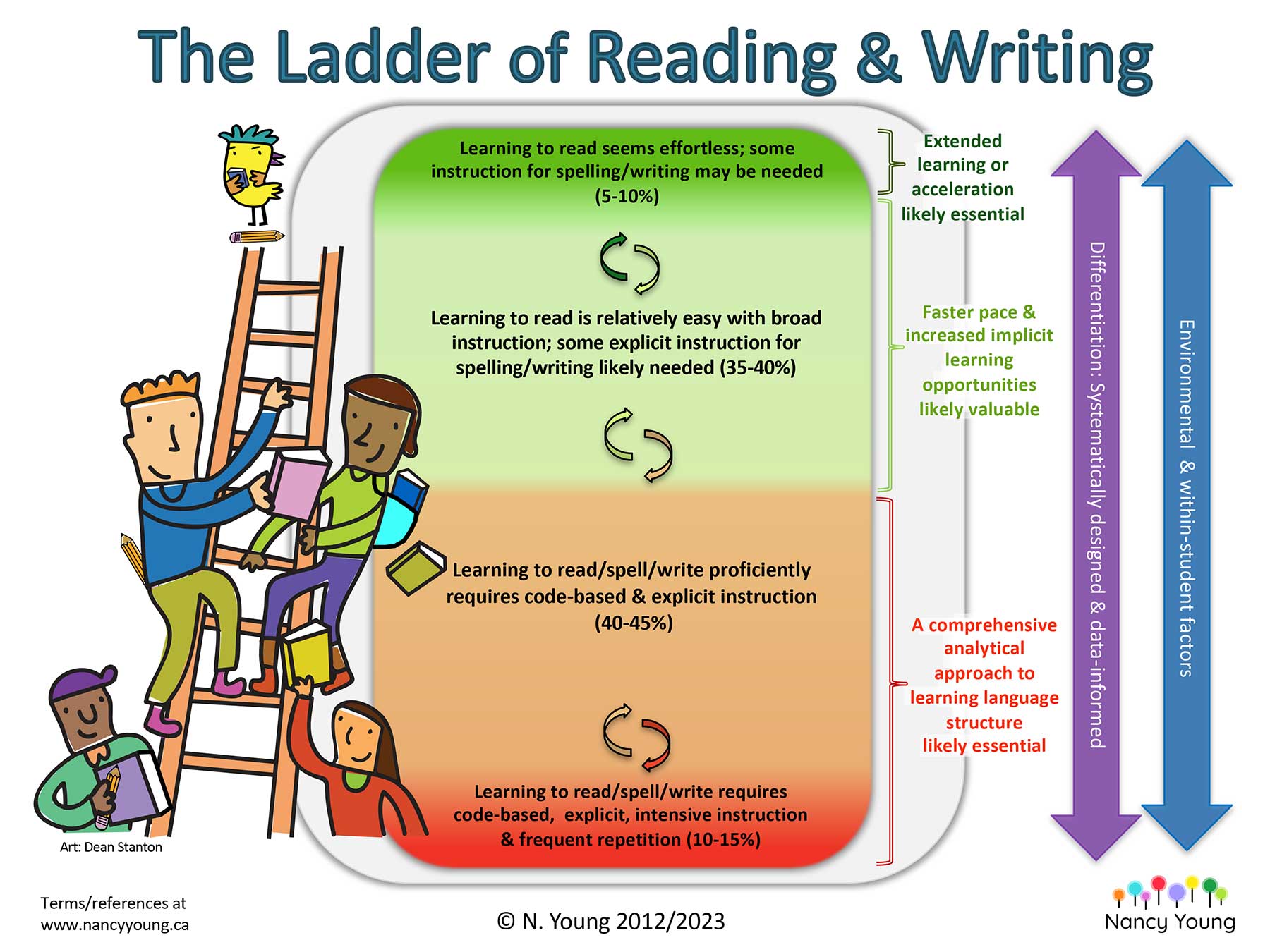

Purple Arrow (words and their order now slightly changed in the 2023 update):

- Differentiation now appears first in the arrow, to emphasize that instruction differentiated based on need is essential for ALL students to progress

- Systematically designed follows, to make clear that wherever an individual student is on the continuum of ease in learning to read, systematic design of instruction will take place to ensure appropriate component(s) of focus (WHAT each student needs to learn – content) and taught in appropriate ways (HOW – matching instructional methods and practice opportunities with the learning needs of each student)

- Data-informed signifies that information indicating skill acquisition underpins the provision of instruction differentiated to effectively meet a wide range of learner needs – data can be obtained using various tools as well as observation (and be aware that the tools used to gather data about students in the dark green must be appropriate for students who are already reading – these students do not generally need to be tested on isolated phonemic awareness skills)

Blue Arrow (fewer words in the 2023 update):

Environmental factors encompass

- teacher/school

- literacy in the home

- language/dialect

- economic circumstances

Within-student factors include

- attentional disorders

- psychological disorders

- exceptionalities (e.g., dyslexia, specific reading comprehension disability, developmental language disorder, intellectual disability, intellectually gifted/advanced)

Coloured Continuum – Wording (slight changes)

- Dark green area – changed wording: some instruction for spelling and writing may be needed

- Light green area – added word: some

- Red area – removed word: systematic (this term now appears in the purple arrow)

Coloured Continuum – Colouring and Percentages (slight changes)

- Light green – approximate range now provided 35-40%

- Colouring of light green and orange areas – adjusted slightly to better reflect the “continuous distribution” of learners’ abilities/needs (Boada et al., 2002; Fletcher & Miciak, 2019)

Wording Beside the Coloured Continuum (some changes beside each area)

Beside dark green – changed wording to “Extended learning or acceleration likely essential”

- Extended learning – This term encompasses extended learning of content (e.g., deeper comprehension of more complex text) or enrichment (e.g., guided inquiry delving into interest area)

- Acceleration – This term encompasses early entrance to Kindergarten, skipping grade(s), and subject-area acceleration (learning with students in a higher grade) (see Colangelo et al., 2004)

- Beside light green – changed wording to “Faster pace and increased implicit learning”

Implicit learning for reading/writing is also connected to “statistical learning” (see Treiman & Kessler, 2022) - Beside orange and red – changed wording to “A comprehensive analytical approach to learning language structure likely essential”:

“comprehensive”

- encapsulates approaches/terms currently widely used: “structured literacy” and “the Big 5” or “5 Pillars” from The National Reading Panel Report (2000)

- makes clear instruction is not just phonics but that numerous components of language structure (including morphology, semantics, and syntax) that receive more or less emphasis based on a learner’s need (differentiated content focus)

- is a broader term to avert the association with/use of one particular program/curriculum/approach

- encompasses spoken language development, particularly when this is challenging

- recognizes the importance of background knowledge in skill development

- leaves open the inclusion of additional terms/concepts/approaches under the “comprehensive” umbrella as more research occurs, such as the role of self-regulation (See Duke & Cartwright, 2021)

“Although it seems difficult to move beyond the historic dichotomy of reading instructional approaches, it is time to embrace comprehensive approaches to reading instruction and work toward determining how to integrate different components of reading instruction into classroom practice so that the diversity of students and their individual needs can be addressed.”

(Stuebing et al., 2008, p. 133)

“The most effective programs are comprehensive, integrated with distributed instructional emphasis on the alphabetic principle, teaching for meaning, and opportunities for practice.”

(Fletcher et al., 2019, p. 175)

“analytic”

- entails a strategic approach to teaching the alphabetic principle (letters represent speech sounds), enabling students to be metacognitive about the application of taught strategies to decode/encode, including identification of units of meaning within individual words and sentences (Hoover & Tunmer, 2020)

- emphasizes that individual and combined words within the English language are based on structures that can be logically analyzed and understood (the teaching of that structure – when and how – varying with need)

“Children who attempt to read words by the natural strategy of using partial visual cues will not become successful readers until they adopt the fully analytic strategies that relate orthography and phonology”

(Hoover & Tunmer, 2020, p. 206)“Children who struggle with word recognition require instruction that is highly structured and systematic, including instruction in word analysis skills provided outside the context of reading connected text.”

(Hoover & Tunmer, 2020, p. 251)

“language structure”

- the structure that makes up the spoken and written English language

- is based on the alphabetic code (instruction should NOT teach guessing of whole words – connects to the words “code-based” within the red and orange areas)

- learning language structure entails understanding that:

- the letters (orthographic structure) of a word connect to the sounds (phonemes) heard and pronounced in that word

- letters singly or combined represent morphemes (units of meaning) within a word

- the writing of individual words and words combined in sentences and paragraphs (varying forms of text) is based on established structural conventions

- not every aspect of structure can be taught; understanding that language is based on a structure enables ongoing learning as analytical skills are developed and through exposure to text (See the link to Five from Five below for a good overview of Share’s self-teaching hypothesis)

- the process by which the structure of the code is learned encompasses attention to the meaning and use of the word(s) being analyzed

“The more established our knowledge of a word, the more accurately and rapidly we read it.”

(Wolf, 2007, p. 154)

SOME TAKEAWAYS FROM THE UPDATE

- Differentiated instruction for all students across the continuum should be systematically designed (see purple arrow), encompassing the goals of the lesson(s), instructional sequence, and form of delivery, and considers that “explicitness occurs on a continuum and can take a variety of forms” (Fletcher et al., 2019, p. 100)

- WHO is learning, WHAT they need, and WHY they need this will impact the HOW of differentiated programming design

- Instruction and practice must enable students to move at their own pace, and not prevent them from progressing because they are having to conform to a faster or a slower pace than they require

- For students in the red area (which will include students with dyslexia as well as students with other reading challenges) and the orange areas of the continuum, explicitness and intensity of instruction will vary as per individual needs, as will the component of emphasis (the WHAT) with other components integrated as appropriate

- Although all students should be provided with an environment that offers ongoing “implicit” learning opportunities, some students master skills implicitly while for others implicit learning of certain skills is more difficult; the provision of explicit instruction needs to take this variation into account. Ask: Who needs exactly what explicit instruction?

- Students in the dark green can already read. Their literacy programming, and related progress monitoring, will be different in numerous ways from that required for students still mastering foundational reading skills. Requiring students advanced in reading (AIR), to receive unnecessary instruction may not only delay progress but result in disengagement with learning (Rimm et al, 2018)

MORE BACKGROUND RELATING TO THE 2023 CHANGES

In recent years there has been a whirlwind of change in literacy instruction. Having spent almost two decades voicing the need to get rid of those “guessing strategies”, I’ve felt relief to see that the elimination of guessing (and aligned practice texts) is FINALLY happening. Yet, I’ve also had growing concerns about some of the questionable changes to instruction that have replaced the “guessing” instruction, ways of teaching literacy that educators may be eagerly adopting (thinking they are “science of reading”) yet that may be inhibiting progress for their students.

Back in 2021, I updated my Ladder of Reading & Writing to clarify the differentiation message within my infographic. Unfortunately, my concern about the lack of differentiation has continued to grow since the 2021 update. The swing to teaching phonics the same way to all students, all required to read the same texts, is worrisome. The concerns of Hoover and Tunmer (2020, p. 202) echo my concern:

“…phonics programs that explicitly teach letter-sound relationships… tend to be strongly teacher-centered and have curricula that are rigid with the same skill lesson given to every child in the same sequence regardless of student need. Such an approach to teaching beginning reading conflicts with the basic principles of differentiated instruction… and is either inefficient or ineffective for many children depending on their specific levels of development across the set of reading component skills.”

Linda Diamond, the author of Teaching Reading Sourcebook, recently authored a White paper in which she expressed her concerns about the current swing to “one-size-fits-all”, pointing out that even programs with high ratings may not be appropriately differentiating for the wide range of literacy needs in classrooms:

“To avoid the “one-size-fits-all” approach of whole-class instruction, educators must consider whether

the curricula that currently exist, even those with strong ratings, really meet the need for significantly

differentiated word recognition instruction for struggling readers, young children already advanced in

word recognition skills, and English and multilingual learners.” (p. 5)

Linked to my change of some wording and even greater emphasis on differentiation in the 2023 update, is my concern about the huge time and effort being spent providing phonemic awareness instruction for every single student (sometimes for all grades throughout elementary school) that has taken hold, described as “science of reading”. Dr. Mark Seidenberg explained some of the issues stemming from this “overcorrection” in his 2021 webinar, and other researchers have voiced their concerns. I’ll be writing more about this issue in a future blog post. For now, suffice it to say not all students need phonemic awareness (PA) instruction. Once students can decode, their PA does not generally need to be assessed. Important to know is that the progress of students who are advanced in reading (AIR) may be delayed if they are required to spend time on PA instruction. For those who do require phonemic awareness instruction, letters should be integrated into instruction. (The current wave of teaching PA “listening only” has received huge criticism by numerous researchers.)

My 2023 changed wording also reflects a stance raised by experts in the field – the need to adjust terminology, and include hitherto unaddressed concepts, as the field evolves. An example of an area of research receiving greater attention is the vital role of “implicit learning”. Although all children learn many things implicitly, some children learn aspects of the English alphabetic code far more implicitly than others. Children in the dark green generally learn to read with no formal instruction, yet the implicit learning of literacy skills for children with learning disabilities can be described as impaired (Fletcher et al. 2019). In adding the word “implicit” next to the light green on the continuum, my intention is that this word is the included in the conversation as we address the full range of needs and maximize learning opportunities. Addressing the importance of implicit learning back in 2017, Steve Dykstra’s words cut to the chase:

The dirty little secret of reading instruction is that no matter how much time we devote to it, a huge part of what readers learn occurs implicitly, not explicitly. If explicit instruction is the backbone of teaching and remediation (and it should be), implicit learning is still the biggest part of learning to read…Implicit and explicit learning have been placed in a false competition with each other by widespread misunderstanding…

Finally, although “structured literacy” is still encapsulated under the “comprehensive” umbrella, I hope the term “comprehensive” on the infographic itself will help diminish the current “warlike” statements or feelings generated, where “structured literacy” has been pitted against “balanced literacy”. Overall claims of superiority are purported, despite the reality that these terms are defined in various ways and instruction in the classroom setting (described using these terms) applied in so many different ways. The words of Fletcher et al. (2021, p. 2) capture my efforts to bridge what seems to have become a fraught situation over the last year:

“The appropriate question to ask of a 21st-century science of teaching is not the superiority of phonics versus alternative reading methods, including whole language and balanced literacy, but how best to combine different components of evidence-based reading instruction into an integrated and customized approach that addresses the learning needs of each child.”

My goal is, and has always been, to improve instruction for ALL children. I hope my 2023 update helps everyone using my infographic think more deeply about the use (and sometimes misconstruing) of terminology in our field, and helps bridge to common understandings. I hope my update clarifies even further that we need to serve ALL, and that to do so must take into account who, what, and why…

Every child deserves to learn based on their NEED. As per the purple arrow on my infographic, differentiated instruction systematically designed to support ongoing progress, based on where a child is in skill development, should happen from day one of school. In providing instruction for all students on the continuum, our systematic design must consider the variations in the need for explicit instruction of certain skills and the ongoing power of implicit learning in the big picture.

WILL THESE CHANGES APPEAR IN THE UPCOMING BOOK?

Yes! The book Climbing the Ladder of Reading & Writing: Meeting the Needs of ALL Learners will address in more detail the features and wording within my infographic, referencing the 2023 update.

Co-edited with Dr. Jan Hasbrouck (who continues to be my greatly appreciated sounding board on infographic updates!), the release of this book is expected to be in January 2024. Pre-order information will likely be available this fall. Sign up for my News to receive email notifications.

REFERENCES

Boada, R., Willcutt, E.G., & Tunick, R.A., Chabildas, N. A., Olson, R.K., DeFries, J. C., & Pennington, B. F. (2002). A twin study of the etiology of high reading ability. Reading and Writing 15 (7–8), 683–707.

Colangelo, N., Assouline, S., & Gross, M. (2004). A nation deceived: How schools hold back America’s brightest students. The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development.

Diamond, Linda, Small-Group Reading Instruction and Mastery Learning: The Missing Practices for Effective and Equitable Foundational Skills Instruction, Center for the Collaborative Classroom, June 26, 2023. https://cdn.collaborativeclassroom.org/white-paper/small-group-reading-instruction-and-mastery-learning.pdf

Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56, S25-S44.

Dykstra, S. (2017). A Frank Truth: All Instruction Guides and Supports Implicit Learning. https://dyslexiaida.org/a-frank-truth-all-instruction-guides-and-supports-implicit-learning/

Five from Five (n.d.) The self-teaching hypothesis. https://fivefromfive.com.au/phonics-teaching/the-self-teaching-hypothesis/

Fletcher, J., Lyon, R., Fuchs, & Barnes (2019). Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention, 2nd edition. Guilford.

Fletcher, J. M., Savage, R., & Vaughn, S. (2021). A commentary on Bowers (2020) and the role of phonics instruction in reading. Educational Psychology Review, 33(3), 1249-1274. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8439363/pdf/nihms-1644527.pdf

Hoover, W. A. & Tunmer, W.E. (2020). The cognitive foundations of reading and its acquisition: A framework with applications connecting teaching and learning. Springer.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). (2000). Report of the national reading panel: Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups (NIH publication No. 00-4754). U.S. Government Printing Office.

Rimm, S., Siegle, D., & Davis, G. (2018). Education of the gifted and talented (7th edition). Pearson Education.

Seidenberg, M. (2021, September 26). Part 3: Reading, learning and instruction. [Webinar] Reading Meetings with Mark and Molly: Conversations bridging science & practice. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=adeSgFJ6fkQ

Stuebing, K. K., Barth, A. E., Cirino, P. T., Francis, D. J., & Fletcher, J. M. (2008). A response to recent reanalyses of the National Reading Panel Report: Effects of systematic phonics instruction are practically significant. Journal of educational psychology, 100(1), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.123

Treiman, R., & Kessler, B. (2022). Statistical learning in word reading and spelling across languages and writing systems. Scientific Studies of Reading, 26(2), 139-149.

Wolf, M. (2007). Proust and the squid: The story and science of the reading brain. Harper Collins.